Talking about mashup in animation is straight up something delicate. The logic of creation and experimentation in animation assumes the re-usage of images and the establishment of collage effects, of incrustations; in short, of a visual game necessarily present. But the Japanese animation is even more particular because it extends a certain rhetoric of the borrowing specific to the Japanese culture. The opening and the ending, in other words the opening and closing credits of animes, are good intermediates to approach this move of using external sources while they translate the essence of the unknown animated production current in Japan. Experimental labs on short durations, those credits rely on a complexity of techniques including… of mashup.

An experimental lab

This article will try to decipher the esthetic sense of several existing openings, and to define from it a mashup logic. It will be about valorizing, through symptomatic examples, the recurrent esthetic choices, and from that, translating a story from those credits.

Let’s get ready then, to receive the Japanese plot in the eyes, and a lot of Japanese-Pop (but not only) in the ears.

What is the opening? Those who go over Japanimation enthusiasts’ YouTube playlists can notice the huge space dedicated to those credits, and not only to raise a tribune to the remembrance of a song from their televisual childhood. The opening is a part of the Japanese industry’s logic since a very long time: the song, in particular, is most of the time a full part, interpreted by popular singers, and declined on CDs, DVDs, etc.

In the same way, an opening can push a young group on the front of the popular scene. But beyond the musical interest, the opening is most of all a real space of creation for the studios, and even for some animation producers specially convened to create them.

So the opening has to establish the tone of the series, to approach some esthetic and narrative characteristics specific to the coming episodes. But also to accomplish the technical feat destined to catch the viewer’s eye right away. This work is therefore most of the time really rhythmic and has become more and more complex with the development of technologies. Therefore, the opening translates a denial of the uniform to draw a better praise of the heteroclite and of the heterogenic.

If mashup insinuates in the Japanese credits, it is particularly seen in the most recent productions. The numeric development helped the credits to be not only in mimicry of the real or of other media elements, but also to transplant directly to exterior sources to develop a montage full of the most diverse mixes. Furthermore, the progressive opening of Japan after World War II, precipitated the entry of exterior cultures, particularly the U.S.’s; and Japan therefore, becomes really quickly one of the light poles of globalization starting at the end of the 20th century. This influence of the other pushes popular creation a lot, and particularly the one of manga and animation.

To clarify that, what happens in the Japanese language is a good example. Japanese has an alphabet totally adapted to foreign words, the katakana, around forty simplified characters with declensions that help transcribing words, foreign expressions, particularly universal ones – therefore most of all English ones. Thus, pronunciation is not respected at all because the original word is completely based on the way this alphabet works. For example, the origin of the word “anime” with an accent on the “e”, is the word “animation” in English, written アニメション in Japanese and pronounced “anime-shion”.

The work, concerning foreign images is the same than the one on this language: there’s a real absence of the scruple to appropriate images and adapt them to a statement, a typically Japanese esthetic. Almost all of the culture is based on this idea and creates more fusions than combinations of influence. There is therefore only rarely acts of direct usage of plans, but almost systematically implants more or less retouched.

We have to note, however, before the Japanese dive, one of the opening credits that, without being a mashup, contributed to the complexification of the others. The creation of the famous Cowboy Bebop during the 1990s, started a considerable new sensibility with the precipitation of cosmopolite stories. Mixing genres and esthetics. It incarnates a new development of the young animators’ and creators’ interest for foreign cultures, and for popular genres like cinema, the American comic, and video games. Its director’s (Shinichiro Watanabe) style continues to influence on the new decade, and other credits from his work won’t deny its use in a mashup.

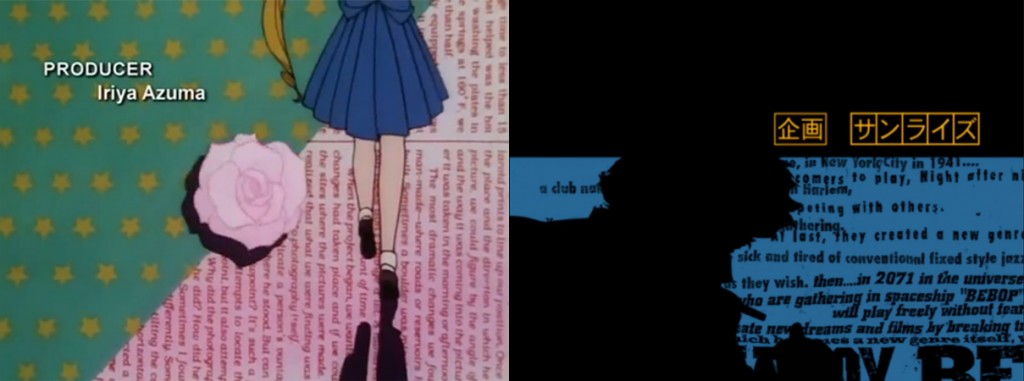

Sailor Moon and Cowboy Bebop

Sailor Moon and Cowboy Bebop

The mashup then becomes really present thanks to the numeric development and the possibility to use graphic effects more easily. But are there any ancestors? One of the opening reflexes consists of a collage of elements, a characteristic that can be found especially in one of the kids’ series because it offers a spontaneous and playful report to the eye.

During the 70s, it was perceptible in Lupin The Third, a show that tells the incredible adventures of the famous gentleman thief’s imaginary grand son. The credits of Lupin appear as a bit precursor when it comes to the actions of collage, since the shots keep getting divided and pushed away from one another in several textures. But the trend comes up mostly in the 1990s. Therefore, Sailor Moon’s theme song juxtaposes washis – those famous Japanese patterned papers used for origami for example – and cuts of western newspapers. In the same way, Crayon Shin-Chan’s borrows from the manga it comes from. This show, unknown in France, is one of the most popular in Japan. It follows the adventures of a young boy with a curse language. It introduces its main character using his silhouette coming straight from its original drawing.

One of the first actions that could be qualified as a mashup, in a small way however, is that collage of different parts. The background always receives patterns coming from somewhere else, silhouetting and juxtaposing to the beat of the songs. This effect extends the use of trams in manga, these arrangements of shapes used to give texture to the sets and to the characters’ details, or even to create playful contrasts. A lot of theme songs of shojo (cartoons for young girls) use washi to deploy a decorative aspect.

Other more interesting backgrounds indicate a more precise origin, and are as soon a more assumed mashup practice. The painterly patterns, in relation with Japanese art, come up profusely in series that are deep in the old Japan. This is the case with Samurai Champloo, the second series of Cowboy Bebop’s director. Little anecdote, the theme song of this show was produced by Mamoru Hosoda, future director of Ame and Yuki, and director of the freshly out The Boy and the Beast. The protagonists are introduced on a background of Japanese prints, while comes up the contrast between sound and image that goes on during the whole anime. The reunion of ancestral Japan – with its prints, its kimonos and swords – and of Nujabes’ rap announces straight away a narrative revisiting this contemporary musical genre through samurai’s’ conflicts.

Picture from the late Dronten Ni Warau who extends Samurai Champloo’s work

Picture from the late Dronten Ni Warau who extends Samurai Champloo’s work

However, old patterns mashup can be surprising and completely offbeat. The 17th theme song of Naruto Shippuden’s saga is the only example of mashup in the series, among “more classical” openings. Real studio fantasy, this theme song slices through because a game between calligraphic art, Japanese stamps (like Hokusai’s Wave) and fictional elements, establishes.

An integration of the real-life shooting in animation

In those theme songs also cohabitate elements from the real life shooting. The series that takeover science or that belong to the cyberpunk genre are the best example on that level, because technological objects and works with formulas directly integrated, get mingled in it. A lot of creations from the 2010s develop an esthetic neighboring actual data, to build a more serious, almost realistic speech, about scientific drifts or dystopian societies. For example, Ergo Proxy is a part of this trend, as well as Ghost in the Shell, Lain or Psycho-Pass. Its theme song incorporates abstracts of manual extracts in several languages as well several scientific schemes. The editing however makes the identification of data, that appear punctually and are exploded by numeric effects, complex.

The esthetic of those animes implies an image ratio multiplied and diffuse. The theme songs deploy in that logic, games of layers’ fusion where elements, such as clues, scatter and arise by details. This works up a secret language that connotes the weirdness of the show.

Through those games of transparency, the level of reality fades in the designed level, getting away from the now obsolete elements collage. Through those theme songs creating confusion between mashupped elements and those really drawn, deploys a speech about the growing virtuality of surfaces.

Ranpo Gitan serves us as a transition because not only those integrated clues exist in a fusional way, but also real life shootings, like the view from a moving train where townsfolk cross a sidewalk. Once again, this transplant of exterior elements establishes a secret language for a series paying tribute to the writer Ranpo Edogawa, one of the authors of the horrific genre in Japan.

The mashup in the opening then also supposes the integration of urban elements. It is more of the buildings, the streets, the crowds, that become parts of the animated body, and that represent almost systematically the 21st century Tokyo. Here is played the marking of a series like Cowboy Bebop, where is going to be deployed the interest for intrigues in major metropolises, and the episodes aligning every time new themes or different genres. The heterogenic and experimental vein can be found in several recent series like Durarara!!, Gurenn Lagan, Kekkai Sensen, or Kill La Kill. In the opening of Bakemonogatari, a series of that kind playing on the exploded narrations, a colored stapler wanders in photographs of Tokyo. The concept, very simple, seems far from the meaning of the series, but already installs those wide spaces that are going to found a part of the film’s atmospheres.

A sense of reference and duplication

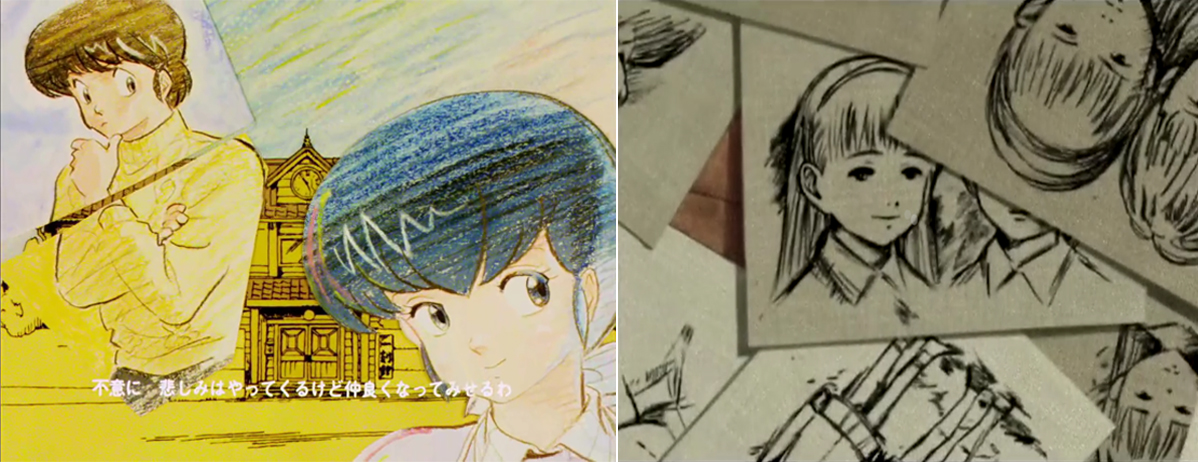

If there’s a mashup, it is sometimes going to take the shape of a wink in the center of the enterprise. Therefore, the presence of sketches or boards of manga, in the heart of the theme song’s densification, is most of the time a tribute to the original piece. It emerges intensely in the endings (ending credits), appearing like a final call, rewarding the original work.

An example from the Maison Ikkoku & Monster’s openings

An example from the Maison Ikkoku & Monster’s openings

This kind of transplant of the original manga can also become a real manifest of the transition to animation. The theme song of Attack On Titans stipulates this that way, through its dynamic mix between manga’s close-ups and technical successions of animation – 2D, 3D, perspectives changes…. – the series imposed itself, when it came out, like a real feat of the I.G. Production studios. The apparition, twice, of those short manga remind us the violent original style, while offering the alternative of an animation equally monstrous.

The pictorial works are also ardently present. They usually build a symbolic relation with the subject of the anime, even if they won’t be a part of the show itself. The incrustation of famous paintings gives us a key about the understanding of the characters, and their degree of use plays with comic and tragic uses. Thus, Klimt canvas brush Elfen Lied’s innocent woman’s body, who became a ruthless killing machine. The imbrications indicate the fragility of the character, or its manipulation by others.

The opening also supposes duplication. Most of the time, protagonists are multiplied, the same silhouettes are doubled in the shot, most of the time to play on the same rhythm as the music, or even to create comic variations.

Extract from the ending of Kill la Kill

Extract from the ending of Kill la Kill

In the idea of duplication, it is the ease of the reuse and transformation of the same compounds shots that constitutes one of the recurrent practices of the limited animation. The use of the same animated loop, on which micro-changes would act, appears indeed way more economical than a total recreation. For example, the same explosions are used, with successive color variants in every episode, in famous science fiction sagas.

One creator pushed this characteristic to the stage of obsession, remaking and mashuping himself (since 1995!): Hideaki Anno with Evangelion, who cannot really be defined as a franchise, but as a same story being permanently replayed, recomposed, restructured… Such a singular case will probably be the subject of a coming article.

Coming back to the opening, most of those use recycling and duplication of images in a search for a renewal of the material. Often, second seasons’ theme songs impose a visit of the emblematic past shots, used in a logic of remembrance. Therefore, Re: Hamatora‘s (the second season of Hamatora’s fantastic adventures) theme song, implies, as we could tell from the name, a remix of the previous season’s images. At the beginning and at the end of the theme song, some shots from season 1 appear one after the other and merge together, as if they were programmed as a rushed viewing of the past events. This recurrent way of doing this often calls for an audiovisual metaphor, projecting the images on moving films, or on viewed screens accelerated or rewound.

To conclude…

Finally, it remains difficult to define a mashup in animation, as well as it is to define a cartography of borrowing games. The hybridization appears, indeed, as constant, between obvious mashups, more hidden others, with more or less shot transplants. Thanks to its short duration and its dynamism, the opening allows however to approach directly some of the esthetic reflexes that will be there in a more diluted way in series or movies. It can then be considered mashup in a certain way, because it condenses a lot of elements, whether they are internal or external to the series.

In the end, this journey sheds light upon the logic of creation of Japanese animation, much closer to real life sources than other animations. In France or in the U.S., graphic styles are usually detached from any reality. Or they are inspired by it and totally disconnect from it. Of course, some exceptions remain, but they are more involved in experimentation or documentation of the animation. On the opposite, Japanese animators get material from a lot of exterior elements and play with that in a more or less supported way. If the mashup is present, it is not as affirmed as the western creators, because it is knead by this culture of the borrowing that is going to use images in the most flexible way.

One of the most original theme songs of those past years, Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei, is concluding our journey. This series, deliciously absurd and amoral, narrates a professor’s woes, who tries to commit suicide, but who is more or less stopped by his eccentric students. The illogic story produces this delirious opening for the third season of the series, in a mashup of original drawings, of Asian icons, of paintings, of photographs, of objects…

And, in the logic of the mashup itself, there is another theme song for the season that offers an even more violent and coarse reuse of the first one’s shots.

Article by Oriane Sidre, translated by Leila Zemirli